I’m in Aotearoa New Zealand and there are several things to write about. Let’s start with current preoccupations:

Tamarillos—sharp and sweet and utterly themselves.

Or boysenberries. I love boysenberries, and they grow them here. My first choice is obviously fresh, but it’s the wrong season. Second option is frozen—no luck there. So tinned is the only way to get my boysenberry fix.

Or. The delicious food I was served on the Northern Explorer, the train that runs from Auckland to Wellington. Forget all those jokes about awful railway catering—sandwiches curling at the edges, meat pies of dubious provenance, the lack of vegetarian options—the catering on this train was local (North Island) NZ produce, well cooked, served by exuberant hosts (who also treated us to Māori songs)—and abundant, seriously abundant. From a slice of feijoa loaf on boarding through breakfast frittata, lunch, a mid-afternoon cheese platter, dinner and a sticky date pudding with ice cream to finish. I didn’t realise when I booked the only available tickets for the day we needed to travel south, that this was a special, food-orientated service: Scenic Plus.

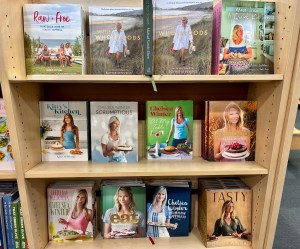

Or. This display I came across when browsing the cooking section of a Wellington bookshop. Every title has a cover that features a youngish woman with long, wavy blonde hair. Make of that what you will.